Island Wines: Part 1

Forget the beaches. Spain's Canary Islands are a paradise for wine lovers.

If I mention Spain’s Canary Islands, you may well think of excellent beaches, sun-soaked beaches, and some of the best beaches in Spain. And you’d be right – it has all three. But look beyond the sand and you’ll find a winemaking region that deserves a lot more attention than it gets.

True, production volumes are low compared to other regions in Spain. Its 44,000 hectolitres[1] of wine per year is a drop in the ocean (excuse the pun) compared to Rioja’s 3 million. But it has a diversity of landscape and a selection of local grapes that few other parts of the country can match. And the quality of its wines is improving by the day

So, join me on a deep dive into what makes this isolated archipelago off the coast of Africa such an enticing destination for the wine lover.

But first, a bit of history

The Canary Islands has a long history of wine production. Some suggest that it was the Canary Islands that the Roman poet Horace was referring to when he wrote:

“let us seek the happy plains and prospering islands, where the untilled land yearly produces corn, and the unpruned vineyard punctually flourishes.” (Horace. Ode XVI to the Roman People) [2]

Even if that claim can’t be proved definitively, we certainly know that by the 15th century, settlers were arriving from the Spanish mainland and bringing with them their precious vines. Initially, production was centred on sweet wines using the Malvasía and Palomino grapes brought from the peninsula. These sweet wines were a hit with passing British sailors and quickly found a market in England. By the beginning of the 17th century, Canary Island wines were so established in British culture that we see references to them in the works of Shakespeare:

“O knight, thou lackest a cup of canary. When did I see thee so put down?” (Sir Toby Belch to Sir Andrew. Twelfth Night, Act 1, Scene 3).

However, as Britain developed closer trade relations with Portugal, wines like Madeira and Port, which were similar in style and often more affordable (being so much closer), began to gain favour with British wine drinkers. Add to that the development of the railway network in Europe making it easier to transport wine – and particularly sherry - from mainland Spain to Britain and it’s not surprising that overseas demand for Canary Island sweet wines began to decline.

But the sector itself managed to survive and today we can find a vibrant wine culture across most of the islands. Still wines make up the bulk of modern-day production, but you will still find some of the traditional sweet wines being made by vineyards such as El Grifo, which we’ll be looking at more closely in the next couple of weeks.

The geography and regions

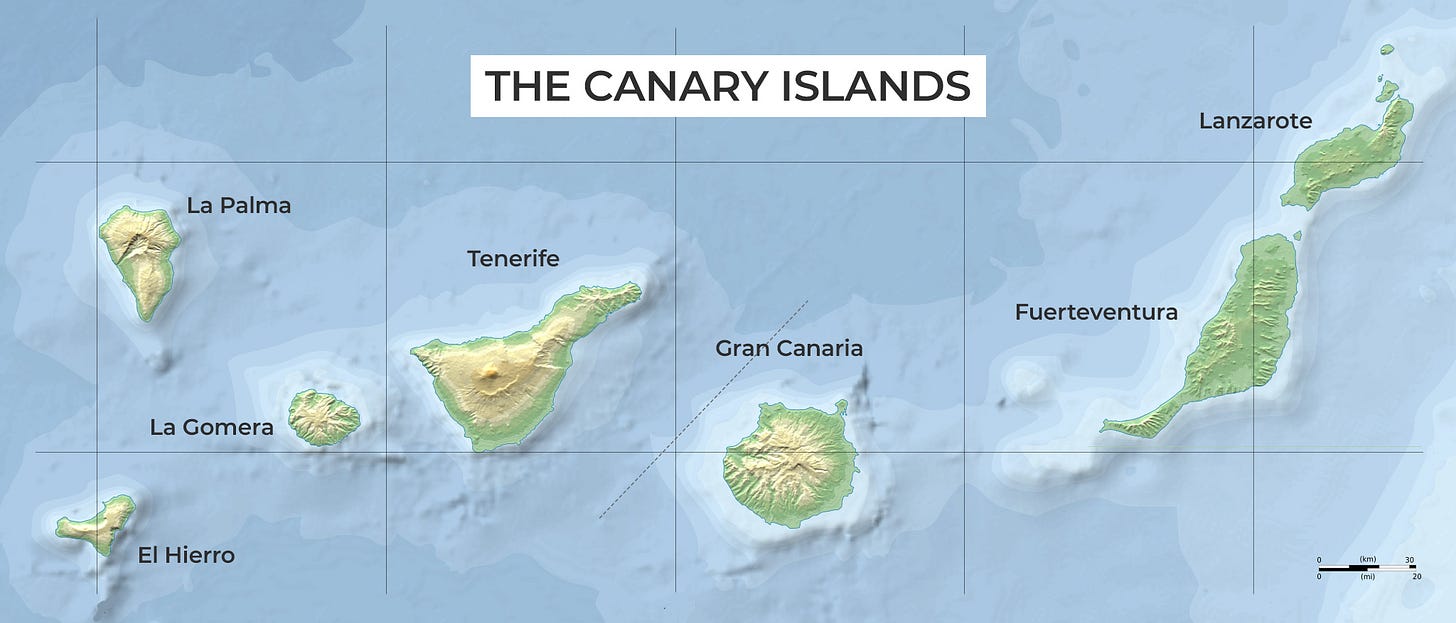

The Canary Islands are located off the coast of West Africa about 1,500km southwest of the Spanish mainland (depending on where you get your ruler out). They were formed over about 25 million years by volcanic activity, which continues to this day, and benefit from subtropical climates and a broad range of landscapes (beyond those beaches I mentioned earlier).

In terms of regions and terroir (or terruño as they say in Spain), the Canary Islands boast more diversity than you can shake a corkscrew at. From a winemaking perspective, the island group comprises ten individual Denominaciones de Origen (the term used to describe official winemaking regions in Spain), plus one overarching classification. And you’ll find vineyards dipping their toes in the Atlantic coasts, admiring the views from the slopes of volcanos, perilously clinging to plunging ravines, or simply soaking up the sun in low-lying valleys. In short, it’s a microcosm of the entire Spanish landscape.

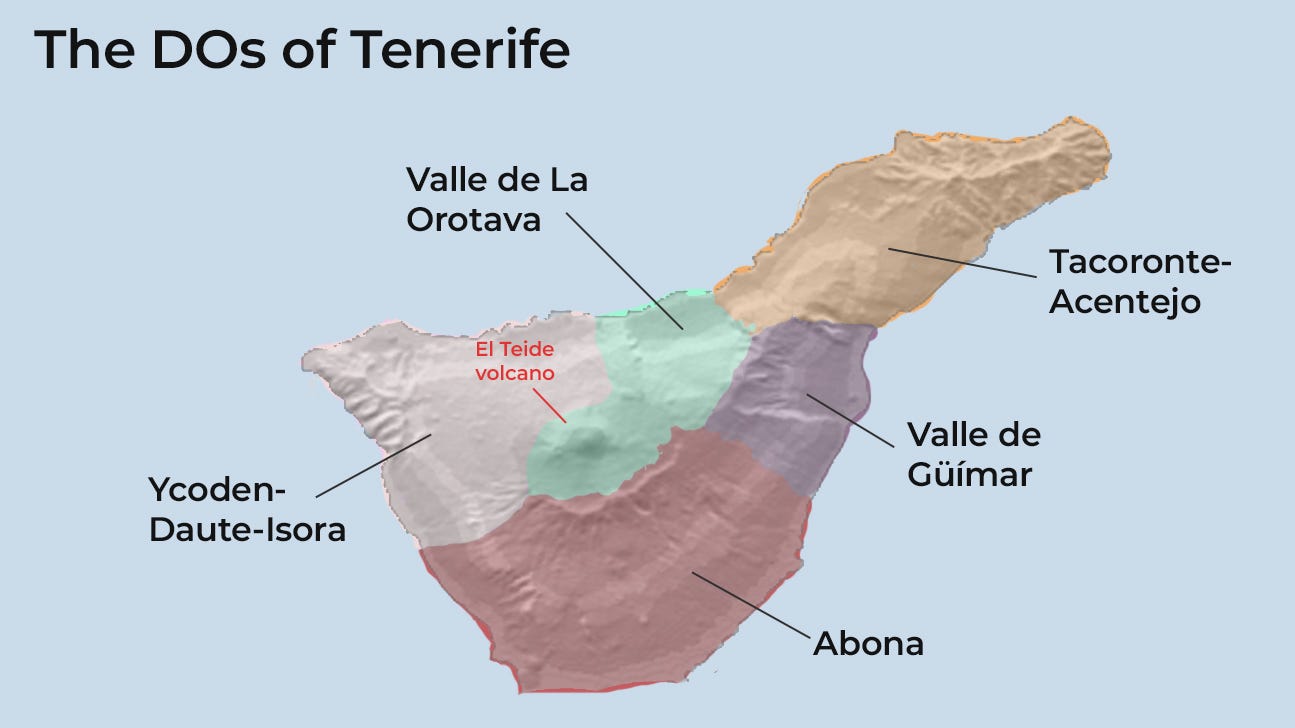

Of the ten individual wine-growing regions, five can be found on the island of Tenerife. This island is famous for its towering volcano – El Teide. With an altitude of 3,715m, the volcano dominates the southern bulk of the island and shapes the different terrains and climates in the surrounding wine regions.

The Denominaciones de Origien of Tenerife (excuse the colouring in – it’s been a while since I was in primary school!)

DO Tacoronte-Acentejo is the oldest DO on the island, founded in 1992. Covering the northeastern tip of the island, this region boasts the highest concentration of vineyards situated at altitudes ranging from 100m to 1,000m above sea level.

DO Valle de Güímar sits between the eastern coast of the island and the western slopes of Mount Teide. Covering an area of 144km2, the land ascends from sea level to around 2,000m offering a variety of growing conditions. But most vineyards are situated between 600m to 800m, providing a degree of stability.

DO Abona is located in the south with many vineyards located in the higher areas. As rainfall is scarce, winegrowers here often cover the surface soil with volcanic sand to retain water.

On the opposite side of the volcano from Abona, sits the DO of Ycoden-Daute-Isora. Again, with altitudes varying from 50m to 1400m, you’ll find a dizzying array of microclimates and a multitude of small plots on steep terraces. That makes for a harvest period that extends from July to October and produces a wide variety of wine styles.

An example of Cordón Trenzado in Tenerife’s Valle de La Orotava

Finally, in the centre of the island’s north coast, we have DO Valle de La Orotava. This DO stretches from the coast to the foothills of the Teide. It’s famed for its unique method of vine growing called cordón trenzado (literally “braided cord”). Here, the vine’s branches are plaited over time to form a stiff trellis, over which new vine leaves and grapes grow. This method enables vines to grow in soil that might not otherwise sustain large plants and also leaves space below for the cultivation of other crops like potatoes.

So that’s a very quick whizz through Tenerife, but what about the rest of the islands? Well, in total you’ve got five more individual DOs, each one occupying an entire island in itself.

To the west of Tenerife are the islands of La Palma, La Gomera, and El Hierro. La Palma is the only island in the archipelago with permanent rivers, and its landscape features small, irregular vineyard plots and vines grown on steep terraces where manual harvesting is the order of the day.

La Gomera goes one step further. With some of the deepest ravines in Spain, La Gomera’s vineyards can often be found growing almost vertically. These days, donkeys have given way to zip lines and cranes for harvesting, but the island still gives meaning to the phrase “heroic viticulture”.

And then you have El Hierro in the far southwest, once thought to be the end of the world. El Hierro has possibly the highest concentration of volcanoes in the whole island chain and along its spine run peaks reaching up to 1,500m above sea level. But most of its vineyards are located along the lower-lying areas and valleys towards the island’s coastline, where they enjoy mild temperatures and plenty of humidity, producing wines with distinctive floral and fruity notes.

To the east of Tenerife, you’ve got Gran Canaria, where vineyard space competes with tourist resorts and other agriculture, but still manages to produce a healthy 2,000 hectolitres a year. In terms of climate, temperatures are very stable all year round, but this is an island of two halves. In the north, you can be sitting under grey skies, whilst to the south they are enjoying the best sunshine in Spain.

Finally, you’ve got Lanzarote. One of the most popular tourist destinations in Spain, this island is famed for its alien volcanic landscape which has led to a unique cultivation method where vines are grown in dips dug out of the volcanic soils and surrounded by low, semicircular stone walls to protect the vine from the Saharan winds that whip across the island. What began as a necessity to enable vines to grow has turned into a landscape-defining feature that has inspired visitors and artists alike.

Low, semicircular stone walls protect vines on the island of Lanzarote

Finally, finally, there is the overarching classification DOP Islas Canarias. This classification encompasses all of the Canary Islands and allows for a wider range of grape varieties and wine styles than the individual Dos. It was founded in 2012 as part of an initiative to consolidate the region and provide an integrated approach to international marketing for many of the region’s smaller producers.

You’ll notice that Fuerteventura is missing from the above round-up. Whilst it used to have a respectable winemaking sector, increased scarcity of water all but finished off the majority of vineyards. Fortunately, projects are now underway to revive some of the old vineyard plantings, so who knows what the future holds there.

Grapes of the Canary Islands

OK, enough about the regions, what about the grapes? Well, here again, the islands are marked by their diversity. The Spanish government lists a total of 28 different varieties being officially grown in the archipelago. These include some common grapes like Moscatel, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. But the wonderful thing about the Canary Islands is that the majority of their grapes are only found here.

At one end of the scale, you’ve got varieties like Breval, Castellana Negra, Forastera Blanca, and the wonderfully named Gual, which are grown in very small quantities. The total plantings of Breval cover no more than a football pitch.

And at the other end, you’ve got the big hitters of Listán Negro, Listán Blanco, and Malvasía which between them account for around 80% of production throughout the islands.

Listán Negro is the most widely grown of the three. It has a natural affinity with the soils and micro-climates of Tenerife, where it produces strong yields of ripe grapes on its volcanic soils. It’s known for its versatility and ability to produce a wide range of wines. On the lighter side, you’ll get young and fruity wines with aromas of red berries, cherry, and plum, soft tannins and a medium-bodied palate. At the other end, you’ll find full-bodied and complex wines, often aged in oak barrels, which can have aromas of dark fruits, spices, and leather, with firm tannins and a long finish.

Alongside Listán Negro in the volume stakes is Listán Blanco. A derivative of Spain’s famous sherry grape, Palomino Fino, Listán Blanco thrives in the Canary Islands, where it’s able to adapt to different altitudes and micro-climates whilst still producing consistent yields, partly due to its natural resistance to disease. In general, it produces light-bodied wines with aromas of citrus, green apple, and tropical fruits. But you will find some winemakers giving this grape a bit of ageing in oak barrels to produce delicious whites with more complexity and subtle notes of honey, toast, and dried fruits. Yum!

Finaly, there’s Malvasía. Actually, there are two Malvasías. Well, in truth, there are three - Malvasía Aromatica, Malvasía Volcanica, and Malvasía Rosado - but Malvasía Rosado only accounts for about 4ha of plantings, so it’s not really in the same league as its two white cousins.

I digress.

Of the two white varieties, the less common (here at least) is Malvasía Aromatica, which accounts for a little over 60ha and is the same grape that can be found in mainland Spain in areas like Castilla La Mancha and Cataluña. But the variety the Islanders will tell you is all their own is Malvasía Volcanica which boasts nearly 1,000ha of plantings. A natural cross between Malvasía Aromática and Marmajuelo, it’s often seen in the wines from Lanzarote and produces full-bodied, fruity wines with touches of minerality.

The wines themselves

So, after all this talk about regions and grapes, you’re no doubt gasping to taste some of the delicious wines these islands come out with. So was I when I visited the Peñin Top Wines of Spain fair (link in Spainish) here in Madrid earlier this week. There wasn’t a massive representation of Canary Island wines, but I managed to work my way through a few local producers who between them gave a good account of what Canary Island winemakers are capable of.

Unfortunately, I wouldn’t do them justice by squeezing them into the last couple of paragraphs here. So you’ll have to wait until next time when I’ll talk you through all the wines I tasted in more detail and give you a few pointers as to which wines to target if you fancy a taste of the Isles.

In the meantime, I hope you’ve enjoyed this quick wine tour of the Canary Islands. If you have, be sure to subscribe for more newsletters (it’s all free at the moment) and tell all your wine-drinking friends to have a read as well. All comments are welcome and I’ll try to reply as soon as possible.

For now... cheers!

[1] 1 hectolitre = 100 litres

[2] This quote is taken from the Gutenberg translation. I’m not an expert in Horace so my apologies if there are, more accepted, versions.