Waiter, what’s wrong with my wine?

A quick canter through some of the most common wine faults you might come across

It’s been a while since we delved into the techy side of the wine world, so this week it’s back to the classroom for a closer look at a few of the most common wine faults.

In the olden days, a lot of wine problems were caused, frankly, by a shoddy approach in the winery and a lack of basic hygiene which allowed bacteria to flourish and meant wine was made and stored in a very unstable environment.

In the olden days, hygiene in the winery was sometimes a bit of a challenge!

Thankfully these days things have improved in leaps and bounds, and if you visit most modern wineries I defy you not to come away impressed with the levels of hygiene and cleanliness. That rigorous approach means that from a technical perspective, nowadays it’s hard to find a ¨badly made¨ wine (though just because a wine is technically well-made that doesn’t mean you and I will automatically like it of course, but that’s for another article….).

Nevertheless, while wine is a wonderfully complex, beautiful thing it is also relatively fragile, and no matter how painstaking and diligent the winemaker, with all those thousands of compounds and molecules floating around there are always going to be things that can go wrong.

The first, and perhaps most well-known wine fault is Cork Taint. This is where a compound known as TCA – or 2,4,6-trichloroanisole to give it its proper scientific name! - forms in the cork, giving the wine a mouldy smell a bit like old, wet cardboard, and suppressing a lot of the fruit. It’s reckoned anywhere between 3-5% of wines sealed with natural cork will suffer from cork taint, although many producers are increasingly using TCA-resistant alternatives, including screwcaps, which avoid the problem altogether. Thankfully, it’s a relatively easy problem to nip in the bud, and if you do get a ¨corked¨ bottle you should have no compunction about sending it back and getting another one.

The chemical structure for 2,4,6-trichloroanisole….fortunately you and I are allowed to just call it cork taint!

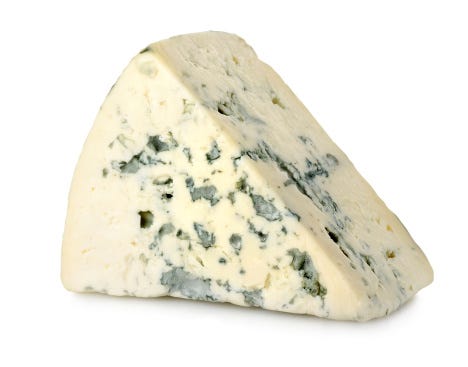

Next up is Brettanomyces which, thankfully, gets shortened to Brett. Brett is a type of yeast that can appear naturally during the fermentation process, especially when wooden barrels are being used, and is best described as adding a kind of funky aroma to wines. At small concentrations this can give wines quite a pleasant, slightly savoury or smoky character, but at the other end of the scale it’s more reminiscent of blue cheese (!) and makes the wine virtually undrinkable. Depending on the wine style the winemaker is after, a small amount of Brett can add desirable complexity to certain wines. As always, it’s a question of degree, so if your wine smells like a full-on farmyard then waste no time and send it back.

Too much Brett and your wine may taste of blue cheese!

Oxidation is one of the most common wine faults and happens when wine is exposed to an undesired level of oxygen, often because of sloppy winemaking, poor storage or because the seal (cork or screwcap) is faulty. Too much oxygen means wines lose their edge as the fruit fades and the wine starts to feel a bit flat on the palate. If a lot of oxygen has got into the wine, the colour may even start to change, with red wines going slightly brown and white wines getting darker. Oxidation can be a particular problem if you’re drinking wines in a bar by the glass and the bottle has been hanging around open for a few days. But remember, some wine styles are deliberately ¨oxidative¨ - if you’re in Spain, think of certain styles of sherries like Amontillado or Palo Cortado which are deliberately aged with lots of contact with oxygen to encourage new aromas and flavours to develop.

Sherry styles like Amontillado or Palo Cortado are deliberately aged with lots of oxygen contact.

At the other end of the scale is Reduction, which is often the result of winemakers taking excessive care to protect their wines from oxidation! Depriving a wine of oxygen can have an effect on the sulphur compounds in it. Sulphur dioxide is often used in winemaking to keep wine fresh and prevent oxidation. But an oxygen-free environment can lead to sulphur dioxide turning into hydrogen sulphide which smothers the fruit in the wine and gives it an aroma of boiled cabbage or, even worse, rotting eggs. If all this is putting you off, have no fear. Often a little reduction can be corrected by aerating the wine, either by opening the bottle and letting it breathe a bit before before you drink it or decanting the wine into another glass vessel so that air can get into it and dissipate any undesirable aromas.

Finally, we’ve got Volatile Acidity (aka VA). This can be a tricky one because, a bit like Brett, at low concentrations it can actually be a desirable thing in some wines. It’s hard to describe VA without getting too geeky, but essentially it’s to do with certain bacteria in wine reacting with oxygen and setting off reactions which produce ethyl acetate. Again, whether this spoils the wine completely has a lot to do with concentration. At lower levels a little VA can help to lift the wine a little and make the fruit sing a tad more; at higher levels, the wine will might off a rather sharp, vinegary aroma, or even take on a slightly chemical tinge which is a bit like nail polish.

There we are, a handful of the most common wine faults you might come across. Remember, if you’re in a bar or restaurant and you think there’s something odd about the wine you’ve been served, don’t be afraid to speak to the barman or sommelier and get his or her opinion. Any venue which prides itself on the wines it serves should have no problem changing the bottle for you.

Cheers!